Haemolysis is a differential for patients with otherwise unexpected anaemia. There are many causes of haemolysis. Thus, instead of indiscriminate extensive investigation, we suggest the following approach.

1. Is My Patient Haemolysing?

The commonly ordered investigations for haemolysis each lack a degree of specificity and sensitivity, although taken and interpreted together, this can be improved.

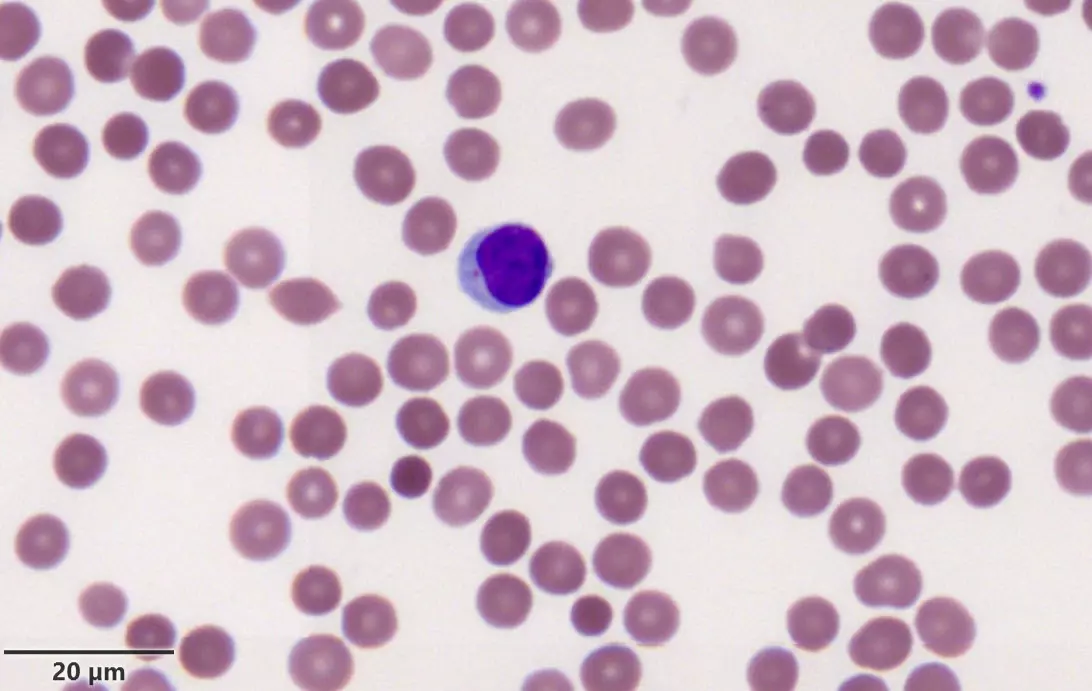

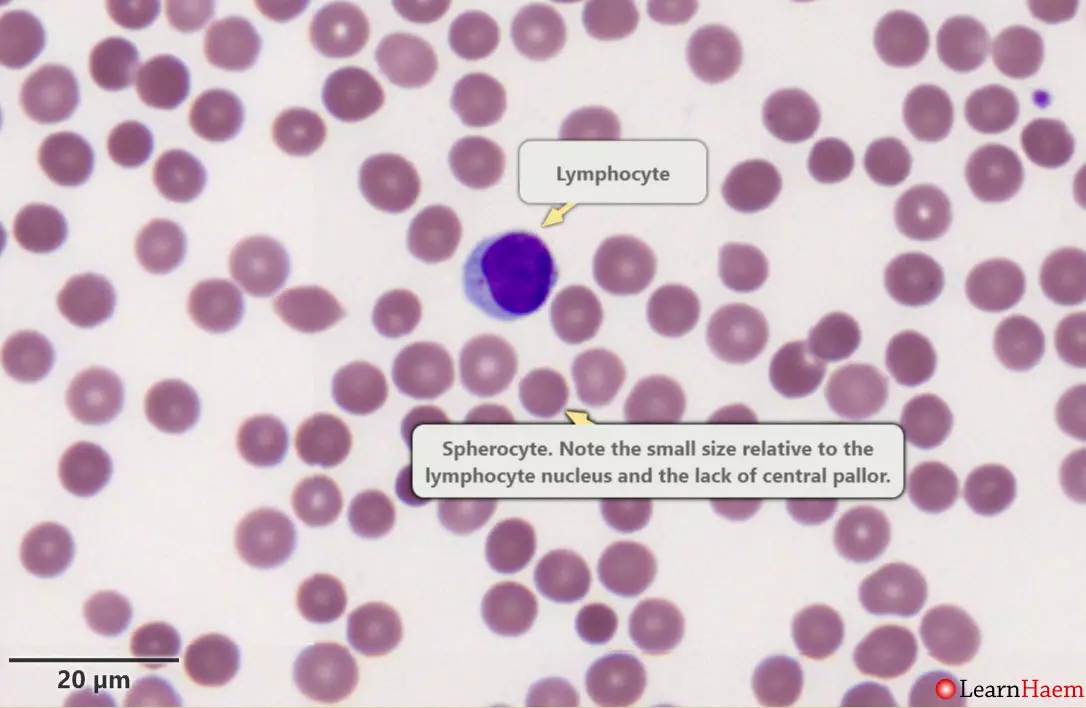

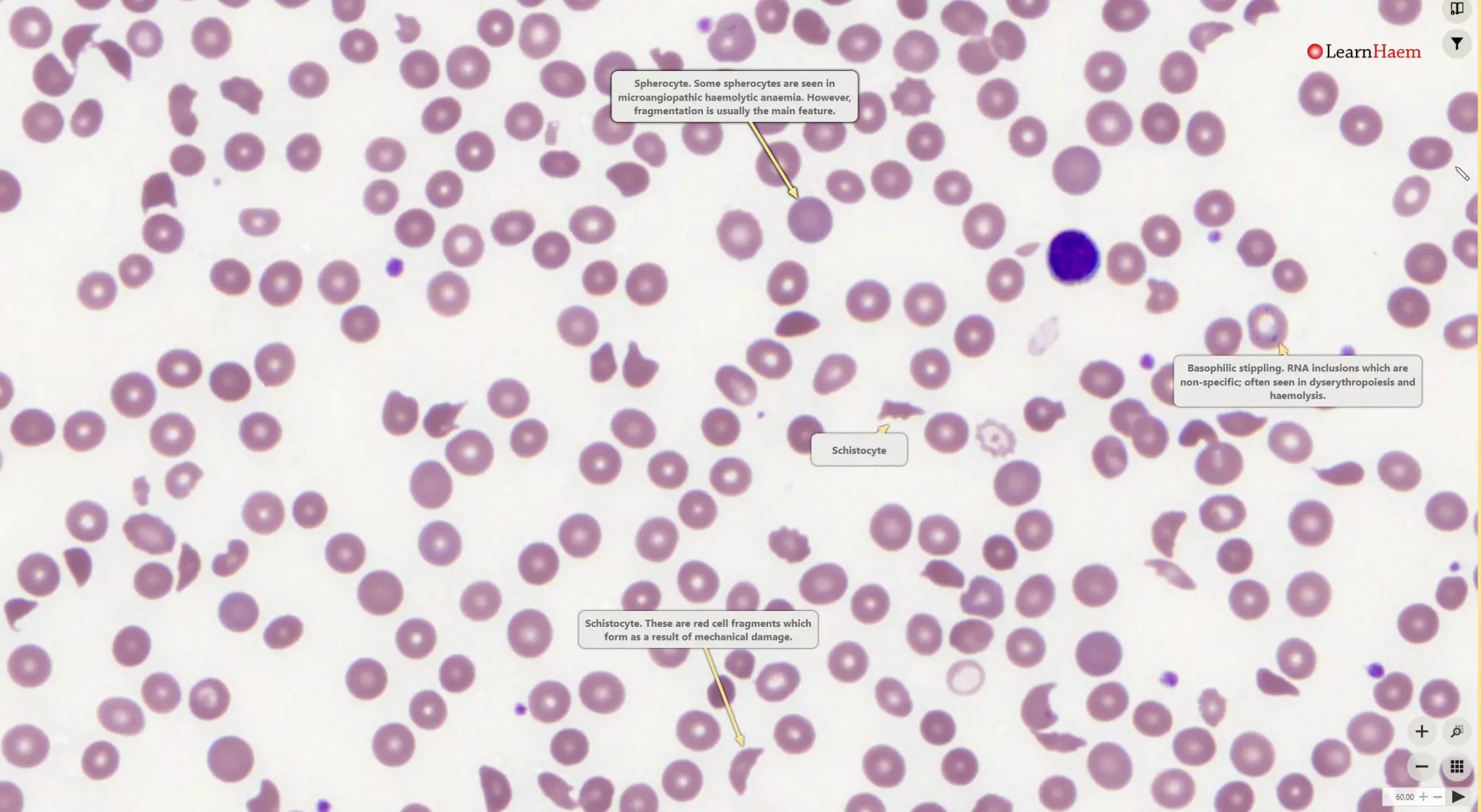

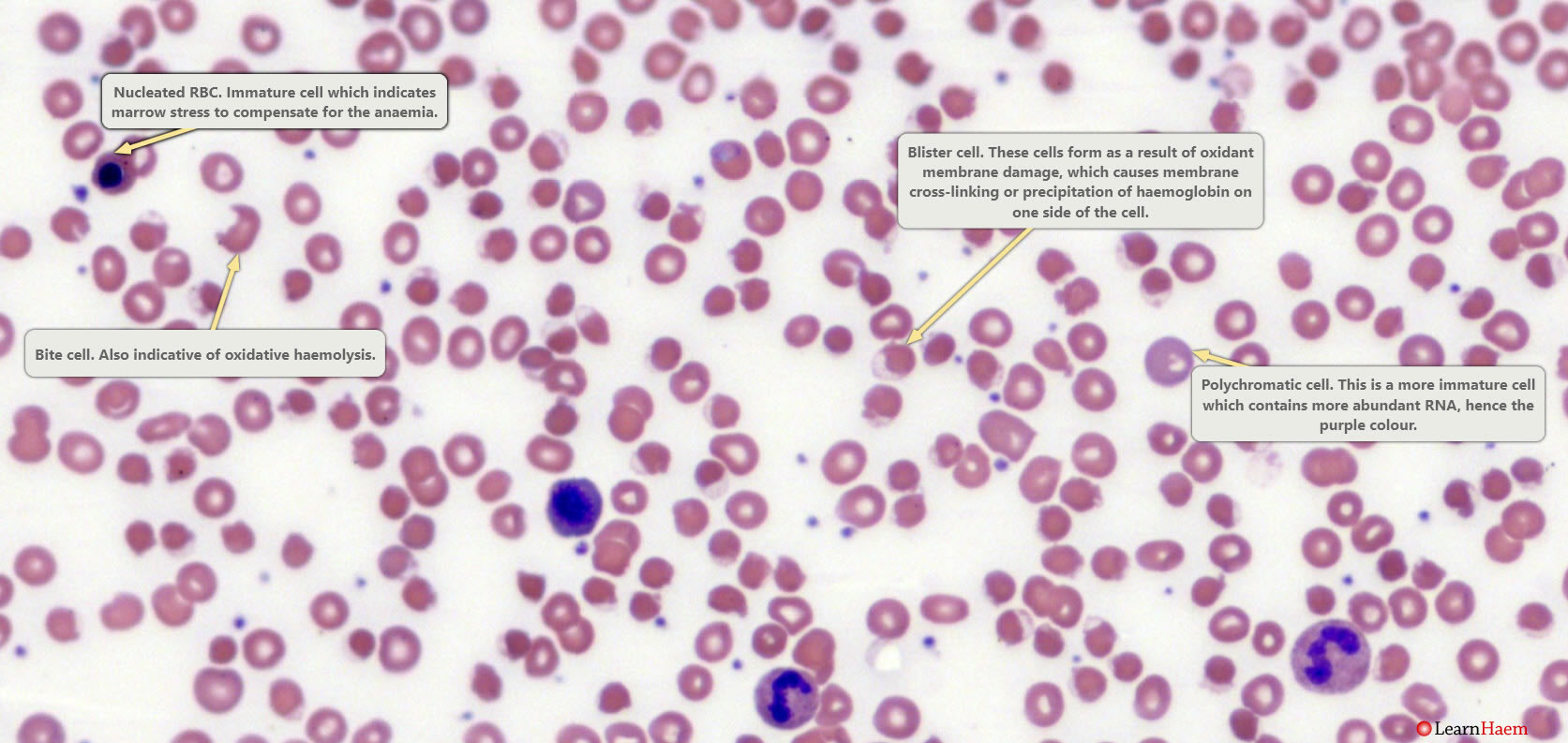

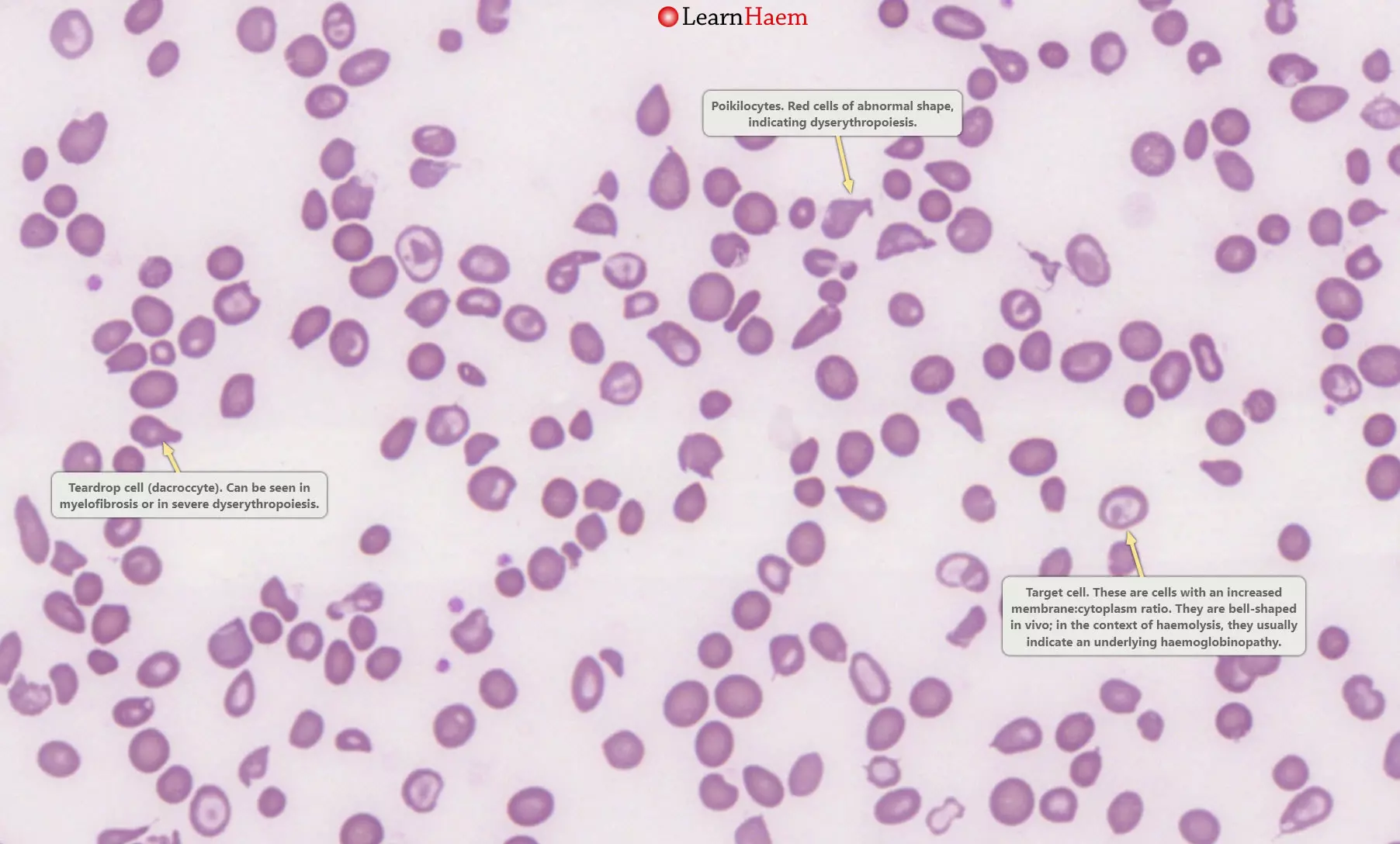

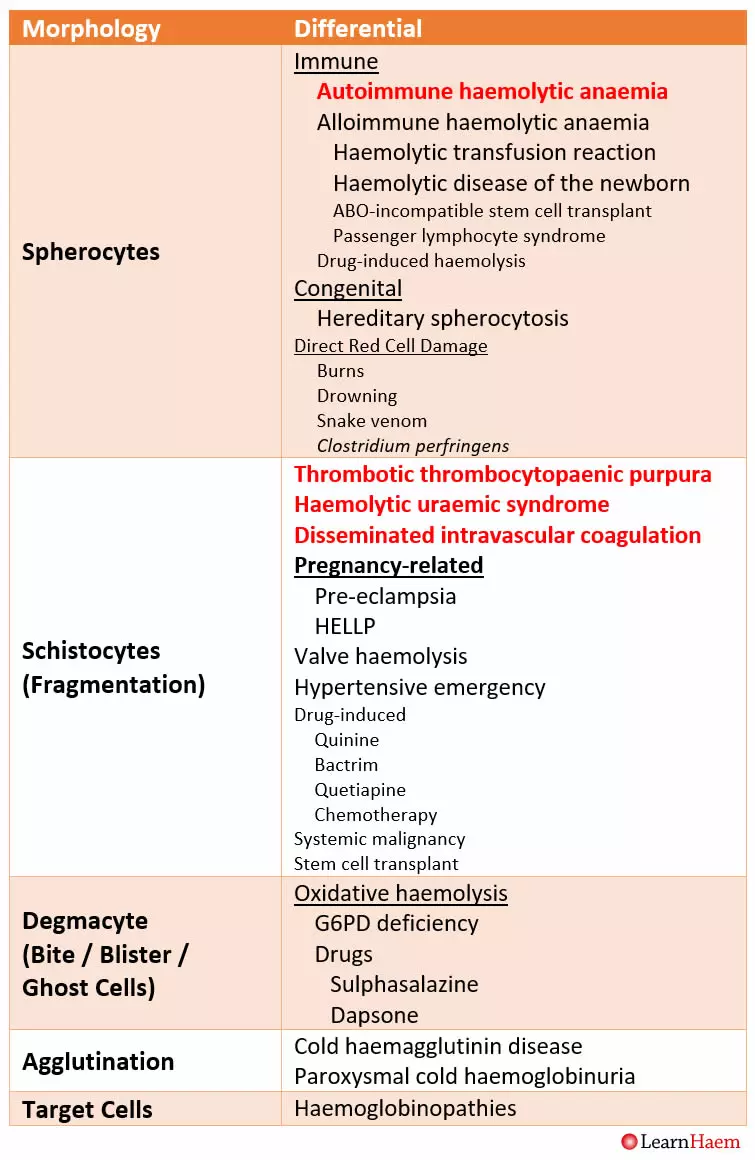

The peripheral blood film is essential for making a diagnosis of haemolysis. In addition, it will also help with narrowing the list of differentials, as different types of haemolysis are associated with different morphological features (see gallery below – click each image to see a full-sized version). The table summarises the differential diagnosis for each morphologic feature of haemolysis.

-

-

Spherocytes. Spherocytes are spherical red cells which have lost some of their membrane, without an accompanying loss in cytoplasm. This is usually the result of a congenital membrane defect, or opsonisation and extravascular haemolysis.

-

-

Schistocytes (fragments). These are seen in microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA), which often results in thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA).

-

-

Blister cells. These are seen in oxidative haemolysis.

-

-

Poikilocytes and target cells. This is a blood film from a patient with thalassaemia major. There are poikilocytes (abnormally-shaped cells), target cells and teardrop cells, which signifies marked dyserythropoiesis.

Morphological features of haemolysis and their associated differentials.

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of heme (see Red Cell Destruction). Hence, levels of bilirubin go up in haemolysis. Bilirubin is conjugated with glucuronic acid once it is taken up by the liver; as haemolysis is a pre-hepatic process, it is usually the unconjugated (or indirect) bilirubin that is raised.

Haptoglobin is a protein which binds free haemoglobin; this complex is removed in the reticuloendothelial system. During haemolysis, red blood cells are broken down. When this happens in the circulation (intravascular haemolysis), haemoglobin binds to haptoglobin, resulting in low haptoglobin levels. Haptoglobin is an acute phase reactant.

LDH is an ubiquitous enzyme with five isoforms. It is a sensitive but non-specific marker of haemolysis. It can be raised in a number of conditions, including acute myocardial infarction, lymphoma, liver disease and any condition associated with tissue damage or a high cell turnover (e.g. systemic malignancies).

To answer the question “is my patient haemolysing”, there should be morphological evidence of haemolysis on the peripheral blood film. In addition, a raised unconjugated bilirubin, LDH and low haptoglobin all also suggest that the patient is haemolysing.

2. Is the Haemolysis Immune-Mediated?

The direct Cooombs test is a simple yet elegant test of immune-mediated haemolysis. Read more about it in the next section.

3. Is There Any History to Explain This?

For patients with immune-mediated haemolysis, a detailed history should be sought, specifically asking about previous exposure to blood products, anti-D immune globulin and certain drugs which are associated with drug-induced haemolysis (penicillins, cephalosporins, diclofenac, methyldopa etc.). Specific symptoms of a lower respiratory tract could point towards a cold agglutinin associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

For patients with non-immune haemolysis, the most important first step is to determine if it is congenital or acquired. Congenital haemolytic anaemias include membrane defects (hereditary spherocytosis, hereditary elliptocytosis etc.,), enzymopathies (G6PD deficiency, pyruvate kinase deficiency etc.,) and the thalassaemias and haemoglobinopathies. There is often a family history of anaemia as the inheritance of hereditary spherocytosis is autosomal dominant and G6PD is X-linked. Patients with haemoglobinopathies may have no family history other than a mild microcytosis.

Leave A Comment